School of Music, ACCAD working toward lag reduction in online music collaboration

Since the coronavirus swept across the country and Zoom meetings have become part of daily life, people have gotten used to lags in the connection that interrupt the flow of a meeting.

What was that? You broke up. I think we spoke at the same time. You go ahead. No, you go ahead.

While that can be a small annoyance that is quickly passed over during a meeting, lag and latency have made live music collaboration virtually impossible over the internet during the pandemic. A single second of lag might not make much of a difference in a Zoom call, but when you’re trying to perform music, you need precision Zoom and other common conferencing software can’t provide.

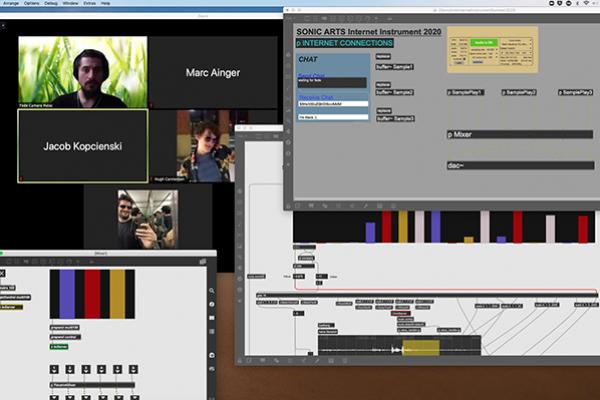

But Marc Ainger, an associate professor in the School of Music, has been working with a team and collaborating with the Advanced Computer Center for Art and Design (ACCAD) since March to develop software that reduces the latency of live audio streams and makes you feel like you’re in the same room as other musicians.

Also importantly, their software increases the sound quality from a highly compressed version you would get on Zoom to uncompressed audio that is CD quality or better.

“It’s very hard to describe what that does for your performance,” Ainger said. “It gives you a presence, and it’s something we’re used to as musicians but we haven’t been able to get on the internet.”

When the pandemic first surfaced, live performance classes across the arts were among the hardest hit. Replicating that feeling of making music together became a problem that needed to be solved.

Some essential questions needed to be addressed for all of this to work: Could they set up central servers that everyone could interact with? Could they write software that would be basic enough to run on older computer systems as well as new ones? With faster internet connections and slower ones? Could the software be simple enough for everyone to figure out with minimal confusion? Could the technology work across huge, international distances as well as it would between neighborhoods in Columbus?

Ainger was already working with postdoctoral fellow Federico Cámara Halac and ACCAD, so a further integration with the center – which conducts research around emerging arts technologies – was a natural fit. Halac and Ainger wound up doing much of the research for the software, and Professor Maria Palazzi, director of ACCAD, helped the team work with ASC Tech infrastructure to install and run servers. But they were just part of the help ACCAD provided.

Among others, Department of Dance Professor Norah Zuniga Shaw was important in providing problem solving, testing and implementation ideas.

“I’m a collaborator,” Zuniga Shaw said. “So when somebody has a great idea and they need me to show up and engage and bring my creative energies to it, I’m in. When there’s an opportunity to pivot toward innovation, we have those kinds of collaborative relationships already established.”

Ainger has been part of a large international effort working on this problem since March. Combined with researchers at Stanford University, the University of California San Diego as well as others in Austria, Germany and Argentina, the software improved over the course of the spring and summer.

In three sessions per week over the summer, the group got together to test different versions. They held weekly improvisation sessions as well, “jamming” with digital music first before improving the technology enough to make vocals and music with instruments possible.

Ainger’s Sonic Arts Ensemble tried out the latest version of the technology when classes began in late August. He had five students in the class, all with various quality internet connections. The results were noticeable to the students right away.

“All that work we’ve done since March to make the software easy and accessible, that was where we had to see if it was going to pay off, and it did,” Ainger said. “The students felt the power of the experience immediately. ‘Wow, the sound is great, and it really is like you’re in the room.’”

With a basic software in place for audio collaboration over the internet, the future possibilities have really opened up. Ainger plans to have live shows using their software later in the fall, with festivals and conferences in Austria, Belgium, Scotland and the United States, but he wants to see where he can push the medium.

“There’s a certain kind of music that you could create on this medium that you could not create other places,” Ainger said. “Rather than say, ‘How can we perform Beethoven on this?’ I would rather say, ‘What can we perform that’s as exciting as Beethoven on this medium?’ What can a virtual concert hall do that a real one can’t?”

More than anything, Zuniga Shaw hopes this technology can help strengthen human bonds. Week by week during the spring and summer, she saw the way live collaboration enhanced the well-being of everyone involved. Humans love making sound together – laughter, applause, singing and music – and that opportunity has really dropped off during the pandemic, she said.

But at this exciting intersection between art and technology, Ohio State is helping to generate new ideas, new work and new knowledge that can bring people a feeling of togetherness they crave even during a time when they are apart.

“Because society at large is now realizing the stakes in our digital lives, there’s a radically enhanced and expanded audience for the intellectual and creative work of this kind of performance,” Zuniga Shaw said. “This is an example of a way that we can and should be pushing on our technologies to be more humane and to advance our lives and well-being, not just corporate profits.”